Blazing a Trail for Reconciliation, Self-Determination & Decolonization

Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia and Canada

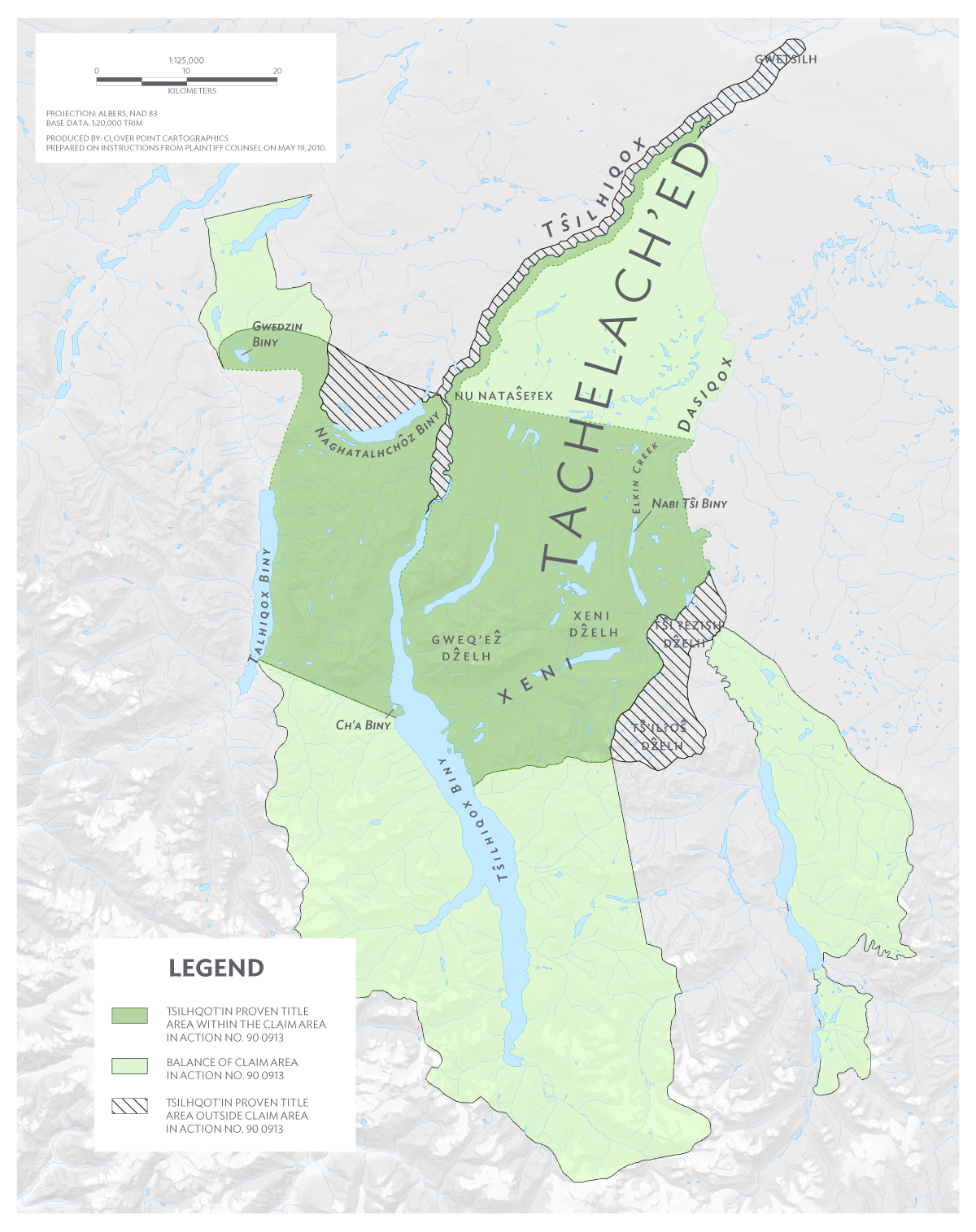

On June 26, 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously declared that the Tsilhqot’in Nation have Aboriginal title to approximately 1,800 square kilometers southwest of Williams Lake, British Columbia. The Court also declared that British Columbia breached its duty to consult with the Tsilhqot’in Nation by issuing forestry licences and carrying out planning activities related to the removal of timber.

For more than 25 years, Woodward & Company has been legal counsel to the Xeni Gwet’in of the Tsilhqot’in. We fought the 339-day trial in the BC Supreme Court on their behalf and on behalf of the Tsilhqot’in Nation and represented them at the BC Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada. We are both honoured and grateful to represent such a courageous Nation through to the successful culmination of this hard fought battle.

On behalf of the Tsilhqot'in, Woodward & Co. LLP are the first law firm in Canada to successfully prove Aboriginal title.

I

History Making Negotiation

A History of the Case

On the thirtieth anniversary of the first title claim filed in Canada, Woodward & Company partner, Drew Mildon speaks to the trial at a workshop in Tofino for First Nations representatives and stakeholders.

Faced with this threat, the Xeni Gwet’in (then the Nemiah Valley Indian Band), called on the five Tsilhqot’in communities to join them in a roadblock to protect the last untouched area of their traditional homelands. On the strength of a promise by then-Premier Mike Harcourt that BC would not allow logging in the Brittany Triangle without Xeni Gwet’in consent, the blockade ended and several years of negotiations ensued between BC and the Xeni Gwet’in to develop a mutually acceptable forest management plan. The negotiations ultimately ended in an impasse and the people of Xeni decided to proceed to court. They asked Woodward & Company to file Aboriginal rights and title claims to their group traplines and Tachelach’ed under section 35 of the Constitution. Eventually the two claims were merged and the action proceeded to court. After considerable legal wrangling, including many pre-trial motions by the Crown, we obtained an advanced costs order. This resulted in the Province and Canada being required to pay costs in advance to the Xeni Gwet’in, allowing this small band of 450 individuals, representing themselves and the Tsilhqot’in Nation, to proceed to trial. Throughout this pre-trial period, a number of important legal precedents were established that will streamline future litigation. These include the right to bring a representative proceeding, the right to sue both the Province and Canada in an Aboriginal title case, the right to proceed against the Crown without having to give notice to all the non-Aboriginal neighbours, clarification on how oral history evidence should be introduced, and many others.

During the course of this trial, Chief Roger William spent 46 days giving oral evidence. His testimony ranged from the importance of legends and the shared Tsilhqot’in oral history to the impact of industrial forestry.

II

Fighting the Good Fight

Aboriginal Rights & Title at Trial

HISTORY CARVED IN WOOD

When the elders speak

Woodward & Company partner, Gary Campo explains the firm’s strategy to prove aboriginal title through the spoken testimony of Tsilhqot’in elders.

“Tsilhqot’in people have survived despite centuries of colonization. The central question is whether Canadians can meet the challenges of decolonization (para. 20). The conclusions I have reached reaffirm the central role of Parliament in matters relating to Aboriginal Canadians. The denial or avoidance of this constitutional responsibility is unacceptable if there is to be a just reconciliation in this era of decolonization (para 1046).

III

The BC Court of Appeal

The BC Court of Appeal

IV

An End to Postage Stamp Theory

Aboriginal Title at the Supreme Court of Canada

“must be careful not to lose or distort the Aboriginal perspective by forcing ancestral practices into the square boxes of common law concepts, thus frustrating the goal of faithfully translating pre-sovereignty Aboriginal interests into equivalent modern legal rights”.

This is an important change from the Court of Appeal decision which held that an Aboriginal group must demonstrate that its ancestors intensively used specific sites and definite tracts of land with reasonably defined boundaries at the time of European sovereignty. The Supreme Court rejected the “postage-stamp theory” and held that Aboriginal title is not confined to specific sites of settlement, but also includes broad tracts of land that were regularly used for hunting, fishing or otherwise exploiting resources.

Building the case, piece by piece

Woodward & Company partner, David Robbins outlines how the case was built from expert witnesses, historical documents, oral history and archeology though to his final argument.

a. A Right to the Land Itself

b. The Role of the Crown With Respect to Aboriginal Title Lands

- that it discharged its duty to consult and accommodate;

- that its actions were backed by a compelling and substantial objective; and

- that the governmental action is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary obligation to the Aboriginal group.

c. The Application of Provincial Laws to Aboriginal Title Lands

The compelling and substantial objective must be considered from the Aboriginal perspective as well as from the perspective of the broader public. To constitute a compelling and substantial objective, it must further the goal of reconciliation, having regard to both the Aboriginal interest and the broader public objective. In our opinion, it will be very difficult to justify any infringement without the consent of an Aboriginal title-holder – particularly given that the Crown retains no beneficial interest in Aboriginal title lands. Before Aboriginal title is established in the courts or recognized by the Crown, the Crown must consult about the proposed land uses, and if appropriate, accommodate the Aboriginal group whose rights are impacted. The level of consultation and accommodation required in each case will continue to be determined on the standard set out by the Court in Haida Nation. However, once title is established, the Crown action will be judged on the higher fiduciary standard of justified infringement. Once title is proven, it may be necessary to revisit past Crown decisions to determine if the Crown has met this higher fiduciary duty.

A personal journey as well

Woodward & Company partner, Heather Mahony speaks to the firm’s years long commitment to finding justice for the Tsilhqot’in peoples and how the experience has changed her.

V

A Precedent Setting Victory

What this Decision Means for First Nations

There are a number of important implications that should immediately guide decision-makers:

A

Aboriginal Title is Territorial

If British Columbia and industry proponents have been negotiating and consulting based on the postage stamp view of Aboriginal title, they will need to re-evaluate their negotiation positions and mandates.

B

Duty to Resolve Outstanding Claims

The SCC has now cautioned the Crown twice (in Haida Nation and Tsilhqot’in Nation) that it is not enough to simply consult and accommodate over unresolved land claims. The Crown has a positive legal duty to actively take steps to implement the direction in Tsilhqot’in Nation about Aboriginal title and resolve outstanding claims through negotiations.

C

Re-Assess Accommodations

First Nations currently engaged in consultation processes should re-assess the strength of their claims to title based on Tsilhqot’in Nation and determine if they wish to submit new evidence and whether the level of consultation and accommodation they are receiving is appropriate.

D

Oral History and Indigenous Legal Traditions Matter

This win was strongly grounded in the extensive evidence brought by the Tsilhqot’in, and in particular, in the oral evidence of the Elders. The trial judge made important findings of fact that met the test for Aboriginal title based on their evidence and on his interpretation of the traditional laws set out in it. It will clearly be important moving forward for First Nations to strategically preserve such evidence in preparation for future litigation and negotiations.

E

Weighing the Economic Interests

Given the potential benefits of an Aboriginal title finding, First Nations will likely want to weigh the cost of obtaining a declaration of title against the potential benefits that would arise from recognized land ownership that includes a broad spectrum of economic benefits and rights.

F

Breadth of Right

First Nations wishing to protect traditional lands from unsustainable exploitation and development now have a much more powerful tool in their toolbox. We expect that, within this new context, injunctions are more likely to be found in favour of a First Nation which has a strong Aboriginal title claim or a claim of infringement of treaty rights.

While further implications will arise in the future, it is fair to say the Tsilhqot’in have won an historic victory in the rights of First Nations to protect, enjoy, and control their traditional lands.

At the scene of the first victory

Woodward & Company partner, Drew Mildon speaks briefly to the successful Meares Island decision and its benefits to First Nations and the environment.